Breaking Bias for Innovation

Smarter Problem Discovery for Commercially Successful New Products

Rushing to solutions hurts innovation! If we don’t break our in-built biases when seeking to solve a problem, we make poor decisions, set off in a misinformed direction and end up building the wrong thing. The risk of failure is very high!

I’ve worked with so many passionate, clever people, who have spotted a problem and are convinced they know how to solve it. But time and again, there’s been a tendency for these founders, entrepreneurs or business owners to rush towards the solution, without taking a moment to check their assumptions, recognise their in-built biases and dig a little deeper into discovering the real issues from the perspective of everyone impacted by it.

But what do I mean by biases? Well, there’s a long list! There’s “sticking to what you already know” (confirmation bias), thinking you’re more right that you really are (overconfidence bias), sticking with a bad idea because you’ve already put time or money into it (sunk cost fallacy) and being swayed by how a problem is described rather than the facts (framing effect), to name but a few! In short, it’s our natural tendency to think about, perceive and interpret a problem in a particular way. And it’s a very useful mechanism for problem solving - providing a cognitive shortcut to help us interact with the world around us, absorb information and make decisions quickly.

We do it without thinking much of the time: we’re not conscious of the fact that we’re using our personal experiences, cultural influences and societal norms to help us process information rapidly. But when it comes to innovation, and developing new products and services, this “automatic” thinking can be highly flawed or incomplete. It will affect how we recognise problems in the first place (which ones we choose to see or ignore), how we frame a problem (how we describe and approach it), and what options we consider and prioritise when we seek solutions.

The Sinclair C5 is a classic example. Brainchild of its inventor, Sir Clive Sinclair, his passion was to develop a low-cost personal electric vehicle for local transport, errands and short pleasure trips (90% of daily uses of conventional cars, which he rightly considered wasteful and expensive). He drove the design and development, setting out the requirements and focusing on engineering challenges such as its battery power to weight ratio. The only external research carried out was with about 60 families in suburban and town environments, to determine whether the steering handlebar and other controls were correctly positioned. On launch, the lack of a human-centred design process became immediately apparent: using it, people felt unsafe and uncomfortable. It was marketed as an alternative for car drivers and cyclists, but appealed to neither! The product failed and the company went bust within months. Sir Clive’s personal biases had steered the development in a direction which was never going to work, failing to consider or understand the needs and wants of his customers.

So how do we mitigate bias in problem discovery? It’s a fairly simple process!

- Seek diverse input - map out and talk to all stakeholders impacted by the problem to learn about their varying perspectives

- Validate assumptions - using data or evidence (either existing or do your own research) to confirm or challenge your initial beliefs

- Reframe questions - explore multiple ways to describe the problem, so that you don’t scupper your thinking before you’ve even started

- Use structured techniques such as open questions, the “5 whys” and empathy mapping to dig deeper and gain greater insights.

If an unbiased (and as we call it, more “human-centred”) approach had been adopted during the development of the C5, research with car drivers and cyclists would have quickly exposed the short-comings in the concept. And this could have been done long before the expensive stage of building engineering prototypes, purely on the basis of sketches and models - a much cheaper and faster way to validate ones assumptions!

Saving time, resources and money, so you tackle the real issue rather than going down a path that’s doomed to fail, is only one of many benefits to unbiased problem discovery. Others include:

- Identifying the root causes of problems, not just the symptoms - so it’s much more likely to lead to solutions which address the real problem, leading to long-term results instead of quick fixes.

- Encouraging innovation and creativity, opening the door to ground-breaking solutions that wouldn’t emerge from biased or constrained thinking.

- Improving perceptions and judgements, leading to better decisions, based on complete, accurate information.

- Building inclusivity and empathy by actively seeking input from diverse stakeholders, leading to more equitable solutions.

- Promoting sustainable solutions that consider long-term impacts, not just short-term fixes, so they are not only effective but also enduring and ethical.

So how do you do it? At the heart of unbiased problem discovery is curiosity, empathy and a desire to learn from diverse perspectives, backed up by real data and reinforced through continuous reflection, validation and iteration. So it’s essential that you approach it with a mindset, and process, that minimises assumptions, brings in the views and experiences of all stakeholders, and relies on evidence and critical reasoning when making decisions.

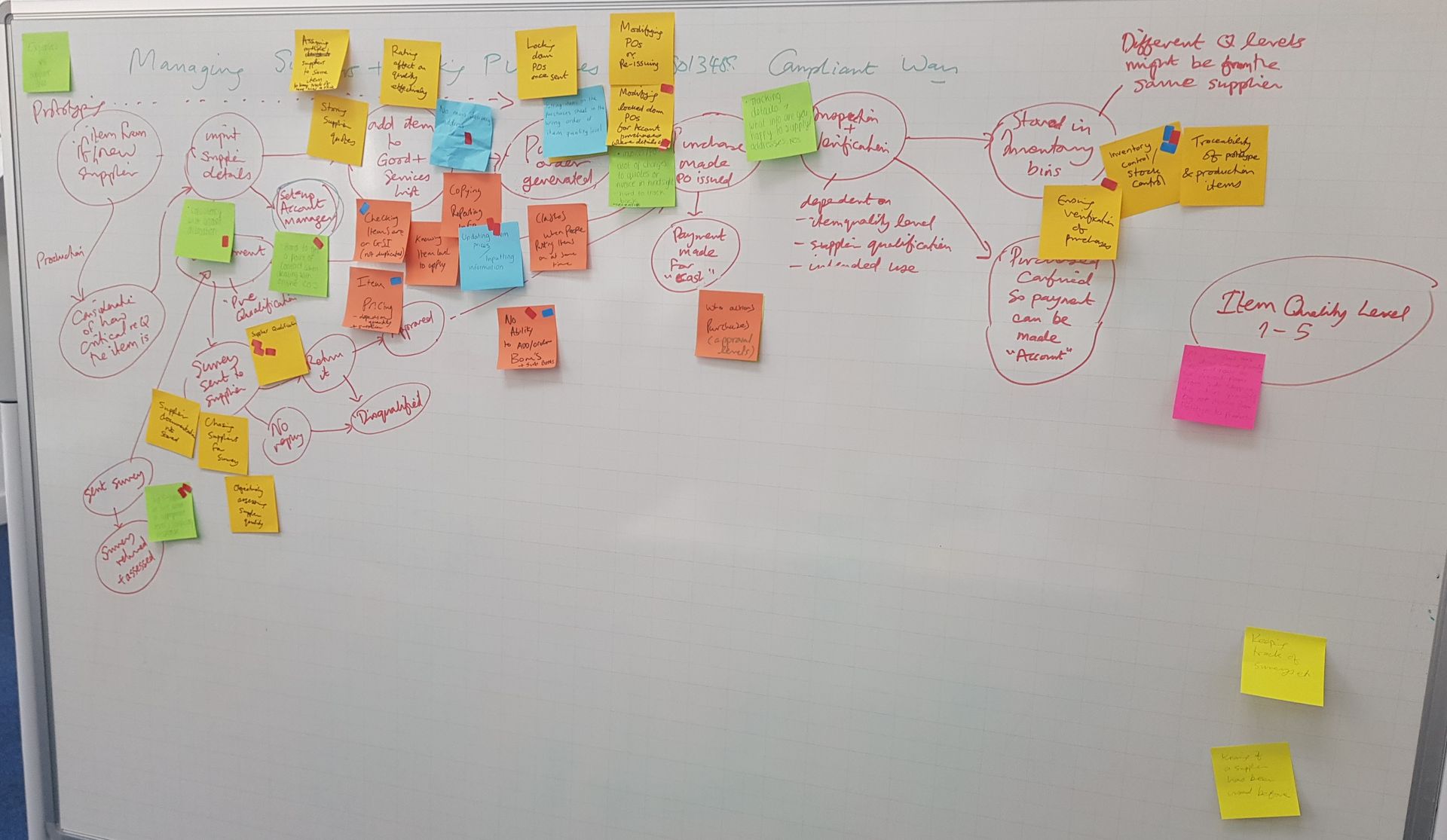

In my work, I usually start by mapping out the “value ecosystem” related to the problem space - who are all the stakeholders and what are the value chains between them (who receives products or services, and who pays for them). This helps surface assumptions that should be tackled early on to ensure any solution is going to be viable.

Another key technique is structured questioning, such as the “5 Whys” or using open-ended questions like “Tell me about your experience of…..” This creates a systematic approach to uncovering the full scope of the problem, ensuring that we focus on facts, challenge assumptions, and promote critical thinking.

Data-driven analysis is also essential - we can’t base conclusions on intuition or what we believe is the case - these must be based on evidence! So we seek out, collate and analyse as much existing data as is available, and use surveys, in-depth interviews, focus groups and observations, to fill any gaps - so we can ground our decisions in reality and reduce subjectivity.

This work often leads to the problem being reframed, as it reveals new ways to define it. And in turn, this reframing opens up new avenues for exploration and prevents tunnel vision.

An example was when I worked with a founder who was the Director of Infection Prevention and Control at an NHS Trust, who wished to reduce hospital acquired infections (which cost the NHS at least £1b a year). He believed that the core issue was improving hand hygiene of staff: the standard approach for assessing this was direct observation of staff on wards, which routinely reported 99% compliance. But his instinct was that this was over-optimistic (when an observer is walking around a ward with a clipboard, it's not surprising that everyone washes their hands religiously!)

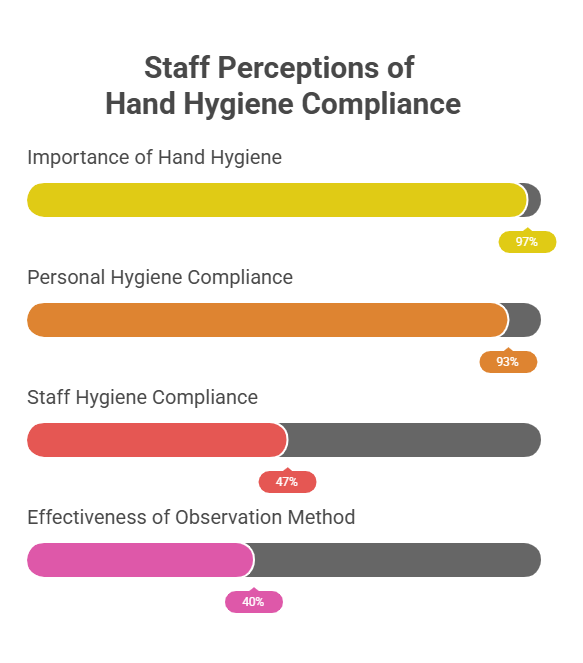

So we ran a Trust-wide survey of 467 staff from across all staff groupings (doctors, nurses, porters, lab staff etc) to explore their perceptions of hand hygiene compliance:

It was clear that staff agreed on the importance of hand hygiene, and interestingly, they were confident in their own abilities to do this well. But their rating of hand hygiene compliance by all staff in general was much less positive, with only 47% rating it as good/very good. As this is the respondent’s perception based on them observing their colleagues day to day (rather than during an official audit), it is likely to be much closer to reality - confirming the founder’s belief that direct observation yields wildly inaccurate results. And in response to the question about how effective they thought the current method of direct observation is, for assessing and improving staff hand hygiene performance, their view was even more jaded, with only 40% rating it as good/very good. The founder was clearly onto something!

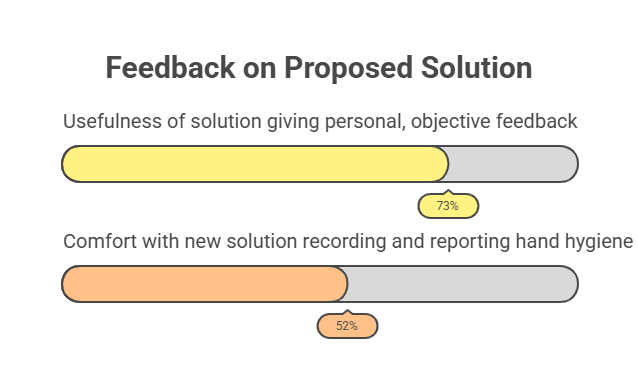

We then asked staff for their views on the founder’s solution idea (a system for giving personal, objective data on their hand hygiene performance in real time), to discover people’s views on its usefulness and acceptability. Perception of its value was encouraging: 73% thought such a system would be useful/very useful. But when asked how comfortable they would be, if it entailed accurately recording and reporting all their hand hygiene opportunities taken (to themselves and their line manager only), the acceptability of this was much less certain, with only 52% saying they would be comfortable/very comfortable with this.

This valuable insight highlighted a key risk to the project, as end-user acceptance would be essential for its adoption. Conversations with staff also made it clear that requiring any change to workflows or patterns of behaviour would present a huge barrier to entry. These learnings allowed us to reframe the problem and rethink the solution, in further consultation with staff. This resulted in a simplified solution design based on RFID sensors in staff badges and receivers placed next to wash stations (so no change to existing workflows was required - staff badges simply had to be reissued for the system to become operational). Individual data was surfaced to each staff member via a mobile app, giving them real time feedback on their performance. And anonymised, aggregated data could be used by team leaders and departments to identify patterns of behaviour and drive improvements on a group-wide basis.

Underpinning all of the above was a fundamentally empathetic approach, where we were driven by a desire to understand and consider the perspectives, needs and emotions of those affected by the problem. There is a concrete benefit in doing this: it helps uncover underlying motivations and challenges that might not be immediately obvious. Crucially, empathy ensures that solutions are human-centered and aligned with real needs - and therefore much more likely to be a long-term success!

If you're embarking on an innovation project, or facing challenges that you're unclear how to solve, book a FREE diagnostic chat to see how I can help!

Charlotte Corke

User-Centred Innovation Facilitator and Startup Advisor